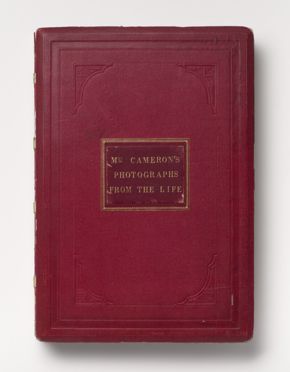

Mrs. Cameron’s Photographs from the Life

Unknown Artist, Julia Margaret Cameron and Her Daughter Julia (detail), 1858, salted paper print, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Director’s Accessions Endowment.

By Malcolm Daniel

The Gus and Lyndall Wortham Curator of Photography

One of the greatest portraitists in the history of photography, Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879) blended an unorthodox technique, a profoundly spiritual sensibility, and a Pre-Raphaelite–inflected aesthetic to create a gallery of vivid portraits embodying a uniquely Victorian sensibility.

In 1863, living in Freshwater on the Isle of Wight in England and about to become an “empty nester,” Cameron received her first camera as a Christmas gift from her daughter Julia and son-in-law Charles Norman, offered with the suggestion that “It may amuse you, Mother, to try to photograph during your solitude at Freshwater.” Cameron was 48, a mother of six, and a deeply religious, well-read, somewhat eccentric friend of many notable Victorian artists, poets, and thinkers.

Photography soon became far more than an amusement. “The gift from those I loved so tenderly added more and more impulse to my deeply seated love of the beautiful,” Cameron wrote, “and from the first moment I handled my lens with a tender ardour, and it has become to me as a living thing, with voice and memory and creative vigour.” The Christmas gift of a camera led to a decade-long career in photography and more than 1,200 surviving images.

Julia Margaret Cameron, Mrs. Cameron’s Photographs from the Life, 1864–69, album of albumen silver prints from glass negatives, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase.

Dedication from the album Mrs. Cameron’s Photographs from the Life, 1864–69.

Julia Margaret Cameron, John Frederick William Herschel, 1867, albumen silver print from glass negative, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund.

Julia Margaret Cameron, The Honourable Frank Charteris, 1867, albumen silver print from glass negative, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund.

Julia Margaret Cameron, Kate Keown, 1868, albumen silver print from glass negative, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund.

Julia Margaret Cameron, Henry Taylor, 1865, albumen silver print from glass negative, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund.

Julia Margaret Cameron, Déjatch Alámayou, King Theodore's Son, 1868, albumen silver print from glass negative, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund.

Julia Margaret Cameron, The White & Red Roses, 1865, albumen silver print from glass negative, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund.

Julia Margaret Cameron, Mrs. Herbert Duckworth, 1867, albumen silver print from glass negative, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund.

Julia Margaret Cameron, Devotion, 1865, albumen silver print from glass negative, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund.

A bit shy of six years after receiving that gift, Cameron prepared a gift for her daughter and son-in-law in return—an album of 75 especially fine prints of her most successful images, inscribed with the following dedication: “To the givers of my Camera I dedicate & give these works of this Camera, with all gratitude for the inexhaustible pleasure to me, & to hundreds, which has resulted from the gift.” That very album, descended within the family to the great-great-great-grandson of Julia and Charles Norman, was acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in 2021.

Julia Margaret Pattle was born in Calcutta in 1815, the fourth of 10 children of Adeline de l’Etang and James Pattle, an East India Company official whose riotous life earned him the nicknames “Jim Blazes” and “the biggest liar in India.” Perhaps from him she inherited a strong will and a disregard for convention. As a child, she shuttled between India and Europe and received the bulk of her education in Versailles, where she spent much of her early life with her maternal grandmother before residing more permanently in India from the age of 18.

In 1836, convalescing from an illness at the Cape of Good Hope, Julia Margaret Pattle met scientist and astronomer Sir John Herschel and classical scholar and jurist Charles Hay Cameron, 20 years her senior. Two years later, in February 1838, she and Cameron were married in Calcutta. In the following decade, Charles Cameron rose to the positions of president of the Calcutta Council of Education and member of the Supreme Council of India, and Julia Margaret played an increasingly important role in social and diplomatic circles of British India. When Charles retired in 1848, he, Julia Margaret, and their six children moved to England, where three of her sisters were already living in or near London.

There the Pattle sisters enchanted London society with their beauty and eccentricity, attracting many of the most original artistic, literary, and scientific minds of the day. Victorian writer Anne Thackeray Ritchie described her first impression of “Pattledom,” as the domain of the Pattle sisters was jokingly referred to by poet Henry Taylor: “To see one of this sisterhood float into a room with sweeping robes and falling folds was almost an event in itself, and not to be forgotten. They did not in the least trouble themselves about public opinion . . . They had unconventional rules for life which excellently suited themselves and which also interested and stimulated other people. They were unconscious artists, divining beauty and living with it.”

Julia Margaret Cameron had the essential makings of an artist. Steeped in a knowledge of poetry and literature, she studied reproductions of early Italian renaissance painting, and a number of her photographs carry subtitles such as “in the manner of Raphael” or “after Giotto” or “after Perugino” or “manner of Leonardo.” Most of all she had the deep desire, declaring: “I longed to arrest all beauty that came before me.” What Cameron lacked—and it was probably this that ultimately allowed her to use the medium in so radical a way—was proper instruction in the practical and technical aspects of photography. “I began with no training in the art,” she wrote. Condemned by some contemporaries for sloppy craftsmanship, she purposely avoided the perfect resolution and minute detail that most portrait photographers sought. “I believe in other than mere conventional topographic photography—map-making and skeleton rendering of feature and form,” she wrote to Sir John Herschel. She opted instead for carefully directed light, soft focus, and long exposures that allowed her sitters’ slight movement to register in her pictures, instilling the images with a sense of breath and life.

When it came to the printing of her photographs, however, Cameron’s failure to meet the standards of the day was less intentional, though perhaps indicative of an artist more concerned with expression than technical mastery. In fact, Cameron was a notoriously poor printer, and it is rare to find prints by her that preserve their original tones. The dense areas have often faded, light areas have often yellowed, and other flaws often scatter across the entire image. The Norman Album, despite foxing on many of the mounts and edge fading on a small number of prints, is exceptional in the number of startlingly perfect prints. Cameron no doubt took special care in the selection of existing prints or the gold toning (for greater permanence) of new prints for this special presentation album intended for her daughter and son-in-law.

The Norman Album contains many of Cameron’s most iconic images in each of the three major categories of her work: portraits of famous Victorian men (for instance, painter George Frederic Watts; scientists Charles Darwin and Sir John Herschel; poets Robert Browning, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Henry Taylor, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson; and violinist Joseph Joachim); women—neighbors, nieces, and house servants, for the most part—almost always in the guise of literary or historical figures (for instance, Beatrice, Christabel, Rosalba, Sappho, or The Mountain Nymph Sweet Liberty); and biblical scenes and “fancy subjects” reminiscent of amateur theatricals (King Ahasuerus & Queen Esther in Apocrypha, The Annunciation, Friar Laurence and Juliet, and Paul and Virginia, among others).

In a dozen years of work, effectively ended by the Camerons’ departure for Ceylon in 1875, the artist produced some 1,200 images. Seen with historical perspective, it is clear that Cameron possessed an extraordinary ability to imbue her photographs with a powerful spiritual content, the quality that separates them from the products of commercial portrait studios of her time and the fulfillment of her aspiration “to ennoble Photography and to secure for it the character and uses of High Art by combining the real and the Ideal and sacrificing nothing of the Truth by all possible devotion to poetry and beauty.”

The Norman Album is on view in the photography galleries of the Museum’s Nancy and Rich Kinder Building, open to a new page each month.

See the full contents of Mrs. Cameron’s Photographs from the Life.