The Kodak Era: A Conversation with MFAH Curator Anne Tucker (part 1 of 3) February 17, 2012

When Eastman Kodak Co. filed for bankruptcy in January, the news didn’t just mark a drastic point in a company’s history—it marked the end of an era. After all, the story of Kodak is not simply one of economics, but one of innovation, nostalgia, and heritage. With its invention in 1935 of Kodachrome film, the first commercially successful amateur color film, Kodak forever changed how we view the world.

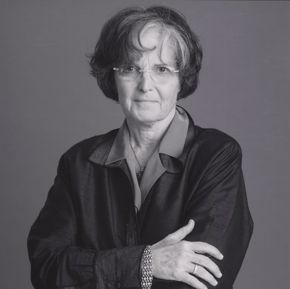

So I sat down with Anne Wilkes Tucker, the Gus and Lyndall Wortham Curator of Photography at the MFAH, to talk about the history of Kodak and the impact of the bankruptcy. She began with her own snapshot of how photography first entered the pop-culture mainstream:

“George Eastman’s contribution to photography was not only to introduce flexible roll film, but to figure out a system where the public could easily take pictures and have them printed by someone else. Amateurs no longer needed to know all the technical components of making prints; they didn’t have to have a darkroom.

"At first, you actually sent your camera back to Rochester, New York, and had the film taken out, processed, a new roll of film put in, and then the whole camera and your pictures were sent back to you. But being the astute businessman that he was, Eastman figured out that he could license that to local businesses. So every small town could have somebody developing your film and selling new film. It opened up the ability to make pictures for millions and millions of people. The other thing about the snapshot is that it opened up having a family portrait to economic classes that never had it before. Most people went to a studio maybe once or twice in their lives before, for wedding pictures or some special occasion.

"Kodak really didn’t have a rival until well into the 20th century. There were companies in Europe and Japan that made paper after World War II, but really Kodak was such a monster. . . . The reason Kodak and Polaroid have gone bankrupt now is that they didn’t understand what was going to happen with digital. Kodak had a digital camera very early, but they just didn’t take advantage of it.. . . . We don’t know yet what the digital scene is going to be.

"But it’s definitely the end of an era that was quite extraordinary and rich. Snapshots are an important part of the history of photography. It’s dramatic with Kodak—that something that huge is gone.”

Stay tuned for two more excerpts from Anne Tucker's conversation, in which she goes on to discuss how snapshots affected art, photography, and history; and talks about the photographic tradition behind the exhibition Snail Mail, on view through May 20.