The Art of Beatriz González October 19, 2019

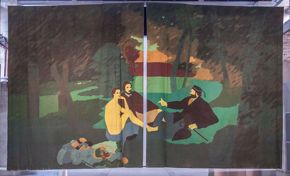

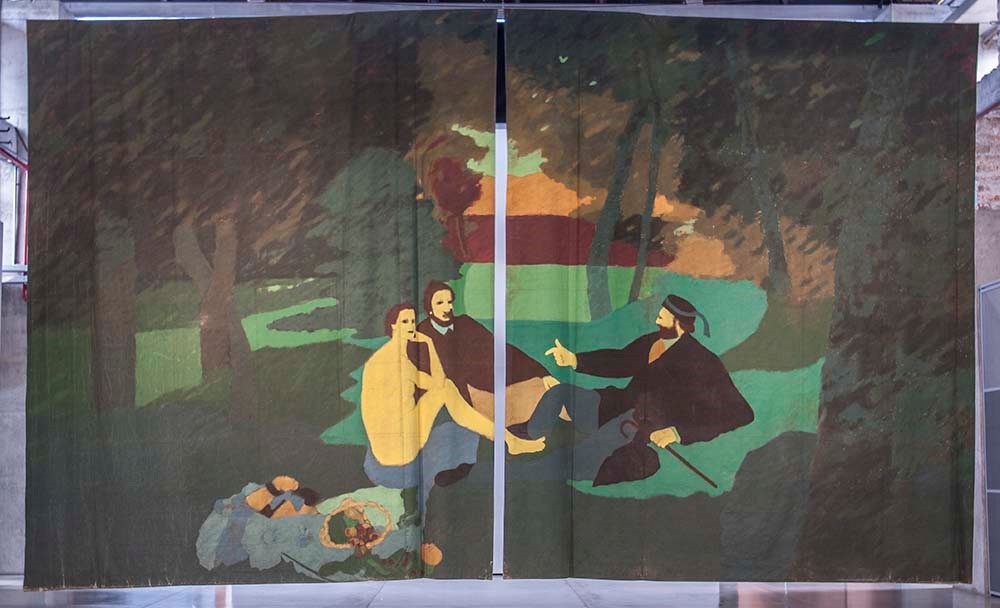

Beatriz González, Telón de la móvil y cambiante naturaleza (Curtain of the Moving and Shifting Nature), 1978, actylic on fabric, artist’s collection, courtesy Casas Riegner Gallery. © Beatriz González

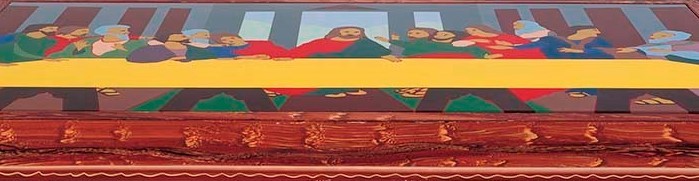

Beatriz González, La última mesa (The Last Table), 1970, enamel on metal sheet assembled on metal table, Tate: Presented by the Tate American Foundation, courtesy of the Latin American Acquisitions Committee, 2013. © Beatriz González

Beatriz González, Sun Maid, 1973, enamel on metal assembly on a tray, MAMU Banco de la República Bogotá. © Beatriz González

The monumental career survey Beatriz González: A Retrospective marks the first large-scale U.S. exhibition dedicated to pioneering Colombian artist Beatriz González.

Over the course of her long and celebrated career, González (born 1938) has engaged in an artistic dialogue with some of the most iconic paintings of European art, as well as with advertising logos and various mass-media sources—appropriating and recasting these images to reflect on the taste for and consumption of Western visual expressions in Latin America.

Iconoclastic Works of Art

Living in Bogotá and well aware of her geographic and cultural position outside of recognized art centers in Europe or the United States, González considers the desire for such images—known primarily through cheap reproductions, kitschy souvenirs, or ads—as extensions of the potent legacy of colonialism.

Characterized by flattened forms and figures, vivid, unmodulated colors, and the integration of everyday objects—including furniture, curtains, wallpaper, and street signs—González’s iconoclastic works critique the power imbalances, marginalization, and cultural colonization perpetuated by the circulation and demand for Western goods and ideas. Employing parody, humor, and irony, she also reflects on middle-class notions of taste, class, gender, and ethnicity, all through the lens of her position as a “provincial painter,” an identity she self-consciously embraces.

• González / Leonardo

In La última mesa (The Last Table) (1970), González creates a stripped-down version of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1498). Her interpretation is painted on enamel on metal, which is in turn mounted on a metal tabletop that has been rendered to resemble wood.

González explained that Leonardo’s celebrated painting was widely known in Colombia through a variety of reproductions, noting that “in every household this image was placed above the main entrance door as a good-luck charm against thieves.” Here the artist questions the cultural and spiritual sustenance implicitly promised by the widespread circulation and consumption of works like The Last Supper.

• González / Manet

In Telón de la móvil y cambiante naturaleza (Curtain of the Moving and Shifting Nature) (1978), González takes on Édouard Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass) (1863). Simplifying, eliminating, or blurring details from the original, she splits the well-known painting of a picnic in the French countryside in half by transferring her more tactile version onto a pair of large curtains.

“The curtain idea came from visiting the dusty Avenue Jimenez in Bogotá,” González explained. “In a shop window I found, next to bottles and snacks, one Salvat magazine with Le déjeuner sur l’herbe by Manet on its cover, ruined by the dirt and sun. It looked like a curtain or a circus tent painted with faded acrylics. That was what came to us from the moving and changing nature so pursued by the Impressionists.” González metaphorically pulls the curtains back to reveal that the relationship with such icons of Western art hinges on illusion and on the viewer’s willingness to buy (or buy into) that illusion.

• González / Sun-Maid Girl

Sun Maid (1974) features González’s deliberately kitschy interpretation of the logo from the Sun-Maid raisins box painted on a round tray, tackling a U.S. consumer icon. Once again painting on an object associated with the domestic realm in her characteristic pared-down forms and bright colors, she omits details like the product name or the “Natural California” tagline that appears on the boxes, relying instead on the viewer’s ability to instantly recognize yet another Western image (and product) that had embedded itself into Colombia’s visual and consumer culture.

The logo’s so-called Sun-Maid Girl has been transformed into a figure with almost disturbing eyes and an unnerving smile. The tray she holds contains blurred grapes that emphasize their artificiality. The unsubstantial, essentially nonexistent offering recalls the empty table or the void behind the curtain in González’s takes on Leonardo and Manet, respectively.

► See Beatriz González: A Retrospective, on view through October 27–January 20.